Ankle Osteoarthritis: Causes, Symptoms, and Treatment Options

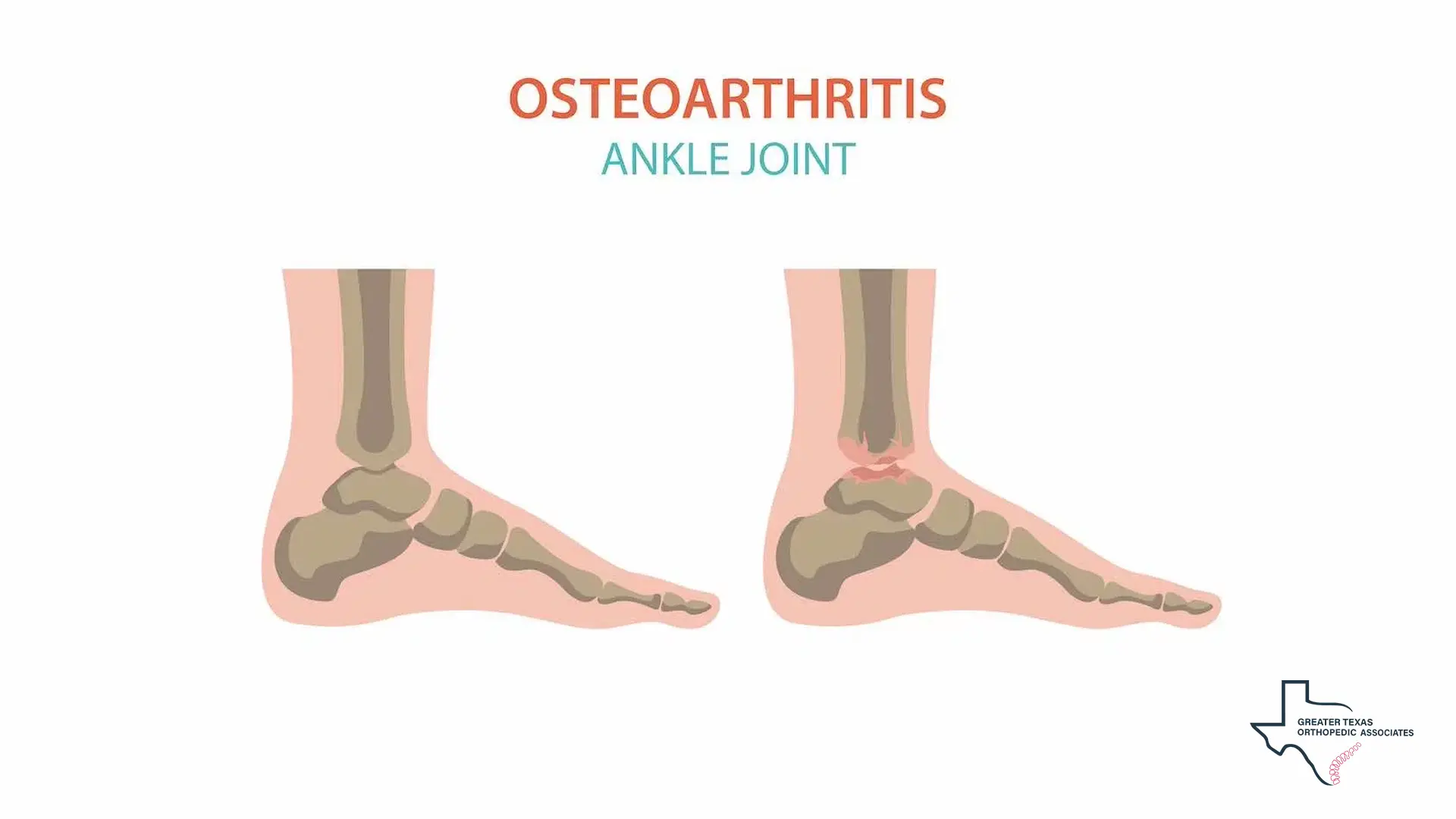

Ankle osteoarthritis is a chronic, degenerative condition characterized by the gradual damage and loss of the protective cartilage that lines the ankle joint. While less common than osteoarthritis in the hip or knee, it can be equally disabling, significantly impacting a patient’s mobility and overall quality of life.

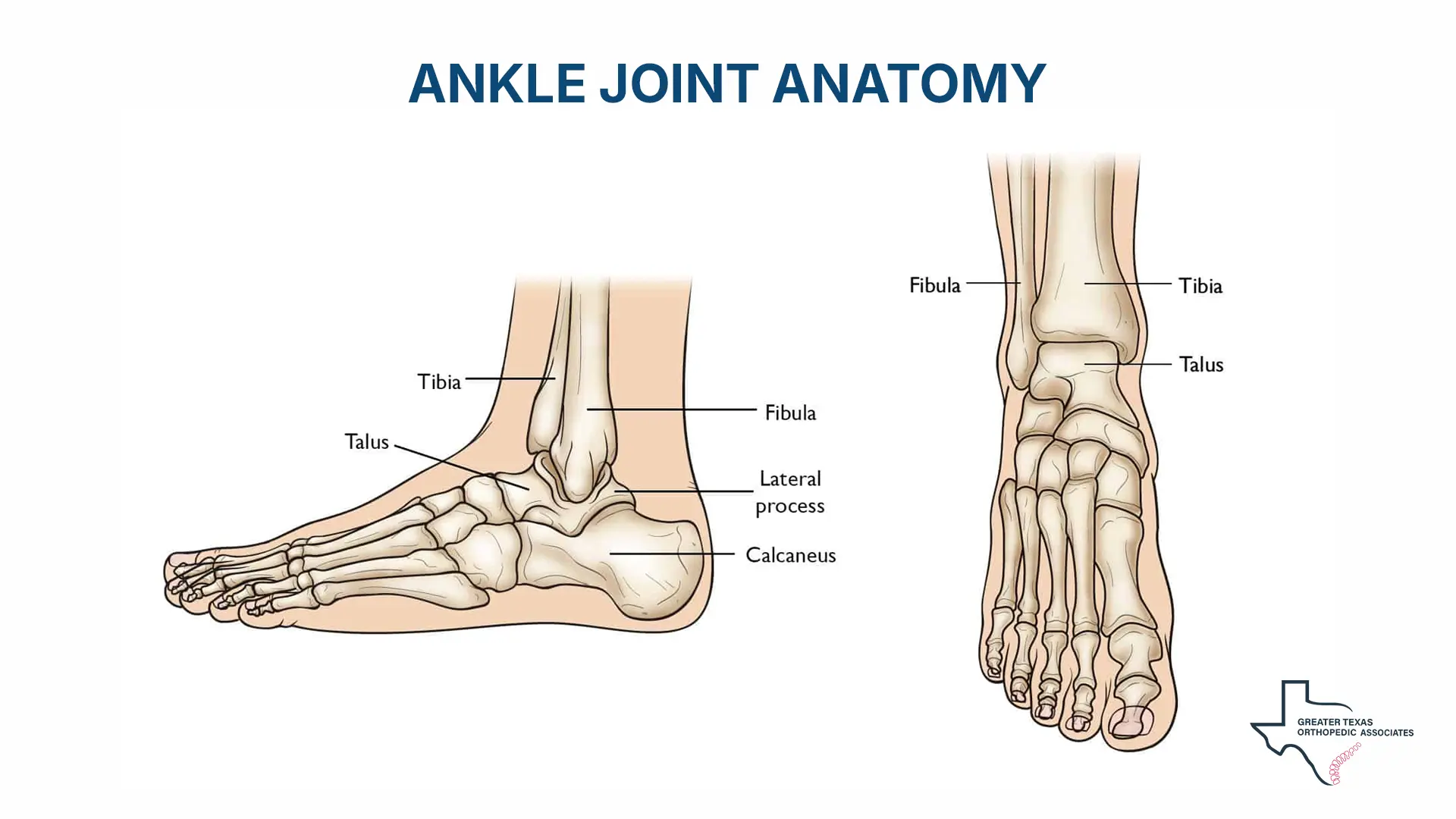

The ankle joint, primarily the tibiotalar joint, is formed by the meeting of the tibia (shin bone), the fibula, and the talus (ankle bone). In a healthy joint, this cartilage acts as a slippery shock absorber, allowing bones to glide smoothly against one another during movement. When this cartilage wears away, the underlying bones may rub together, resulting in persistent pain, swelling, and stiffness.

Understanding the Mechanics of the Ankle Joint

The human foot and ankle are composed of 26 bones and more than 33 individual joints. However, the joint most frequently affected by ankle arthritis is the tibiotalar joint, which functions similarly to a hinge to allow the foot to move upwards and downwards. This joint is subjected to immense physical forces during daily activities; for instance, the ankle cartilage must bear more force per unit area than any other hyaline cartilage in the human body.

Interestingly, ankle cartilage possesses unique biochemical and biomolecular properties that distinguish it from the cartilage found in the knee or hip. It is generally thinner, ranging from 1 to 1.62 mm, compared to the 2 mm or more found in the knee. Despite this thinness, it has a denser extracellular matrix and a higher concentration of proteoglycans, which enhances its load-bearing capacity and makes it less susceptible to mechanical damage under normal conditions. Furthermore, the cells within the ankle cartilage, known as chondrocytes, are often more metabolically active and show a greater capacity for self-repair than those in other major weight-bearing joints.

Recognizing Symptoms and Warning Signs

The onset of symptoms typically occurs gradually. In the early stages, a patient might only feel a dull ache at the beginning or end of a physical activity. As the condition progresses, the discomfort may become more frequent, eventually occurring with every step or even during periods of rest. Stiffness is another hallmark symptom, particularly in the morning or after sitting for a long time.

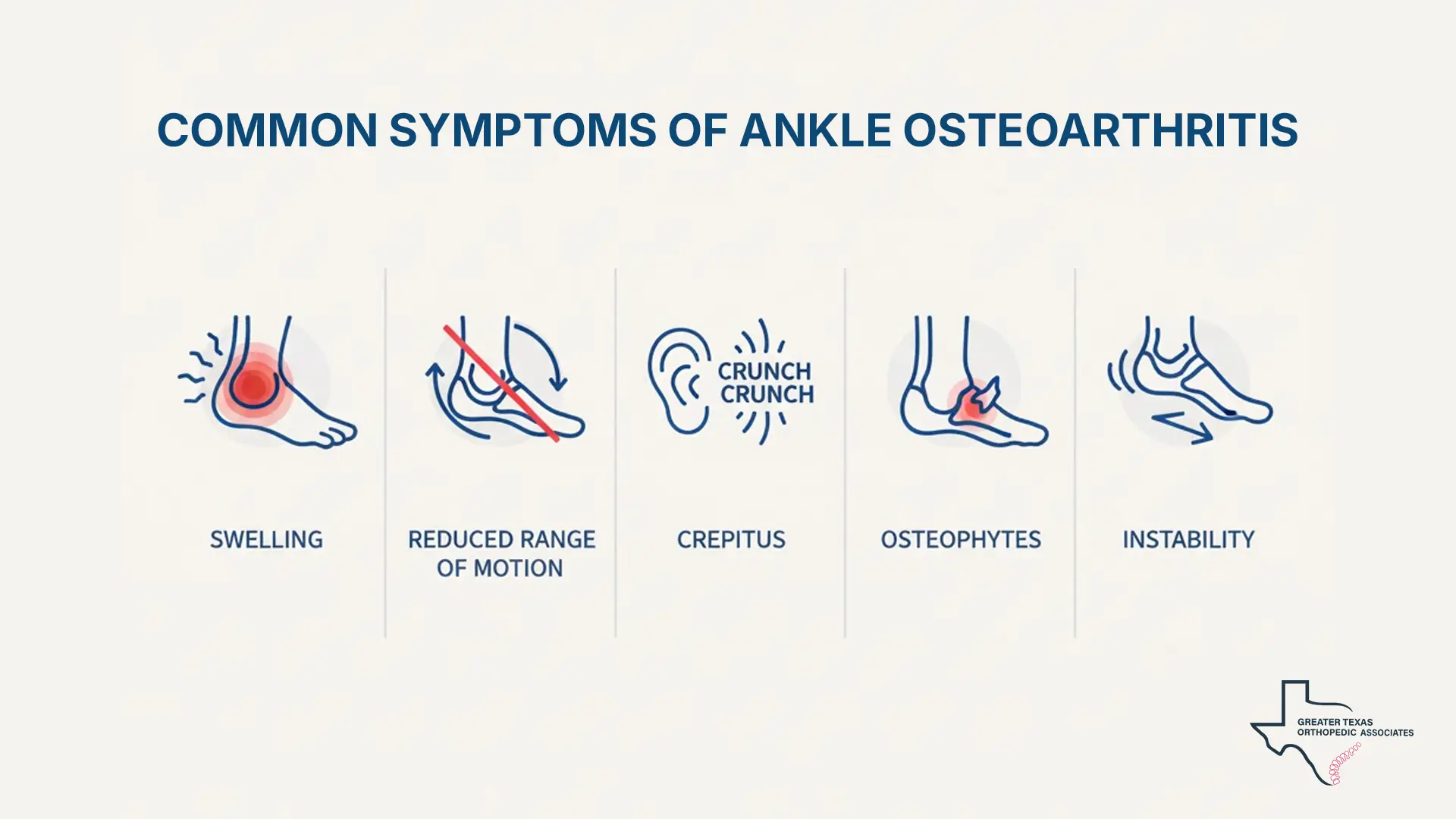

Common Symptoms of Ankle Arthritis

- Swelling and Inflammation: The joint may appear larger or feel warm to the touch.

- Reduced Range of Motion: Difficulty moving the ankle through its full range, such as flexing or pointing the toes.

- Crepitus: A crunching, popping, or grating sound when the joint is moved.

- Osteophytes: The formation of bone spurs at the joint edges, which can lead to “impingement,” where the joint lining becomes pinched during movement.

- Instability: A feeling that the ankle might “give way,” which can increase the risk of falls.

Primary and Secondary Causes of Ankle Osteoarthritis

Unlike the hip and knee, where arthritis often develops without a clear external trigger (known as primary osteoarthritis), the ankle rarely deteriorates without a specific prior cause. Understanding the causes of ankle osteoarthritis is essential, as this condition most often develops secondary to a specific injury rather than age-related degeneration alone. In fact, 70% to 80% of cases are classified as “post-traumatic,” meaning they are secondary to a previous injury.

Post-Traumatic Origins

The primary causes of this condition are past traumas, such as severe ankle fractures (malleolar or pilon fractures) or even repeated severe sprains. These injuries can damage the cartilage directly or alter the joint’s mechanics, leading to uneven wear over time. Because these traumatic events often occur in younger years, patients with this condition are typically diagnosed at a younger age, approximately 14 years earlier, than those with hip or knee arthritis.

Systemic and Mechanical Risk Factors

While trauma is the dominant factor, other causes of ankle joint arthritis include systemic health conditions and structural abnormalities. Rheumatoid arthritis, an autoimmune disease that causes the immune system to attack the joint lining, can lead to rapid joint destruction. Gout, caused by the buildup of uric acid crystals, and hemochromatosis are also known contributors. Additionally, abnormal foot mechanics, such as having very flat feet or high arches, can place excessive stress on the ankle joint. Obesity is another significant risk factor; every extra pound of body weight can add four pounds of pressure to weight-bearing joints like the ankle.

These systemic and mechanical factors represent less common but clinically important causes of ankle osteoarthritis, particularly when no clear traumatic history is present.

Professional Ankle Arthritis Diagnosis

An accurate ankle arthritis diagnosis begins with a comprehensive physical examination and a review of the patient’s medical history. During the clinical evaluation, we assess the joint’s range of motion, check for swelling or tenderness, and perform a “gait analysis” to observe how the patient walks.

In clinical practice, orthopedic evaluations help clinicians assess joint alignment, mobility, and functional limitations.

Imaging and Advanced Tests

Imaging is crucial for a definitive ankle arthritis diagnosis. Standing (weight-bearing) X-rays are the gold standard for visualizing the joint. These images allow specialists to see the “loss of joint space,” which indicates that the cartilage has worn down and the bones are moving closer together.

When X-rays are inconclusive or when earlier stages of the disease are suspected, other tools are used:

- MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging): This is highly effective for detecting damage to ligaments and early changes in the cartilage that X-rays might miss.

- CT Scan: Provides detailed cross-sectional views of the bones, helping to assess complex deformities.

- Image-Guided Injections: Sometimes, a surgeon may inject a numbing agent into a specific joint to see if it temporarily relieves the patient’s pain, which helps pinpoint the exact source of discomfort.

A thorough ankle arthritis diagnosis may also include blood tests if a rheumatic condition like gout or rheumatoid arthritis is suspected.

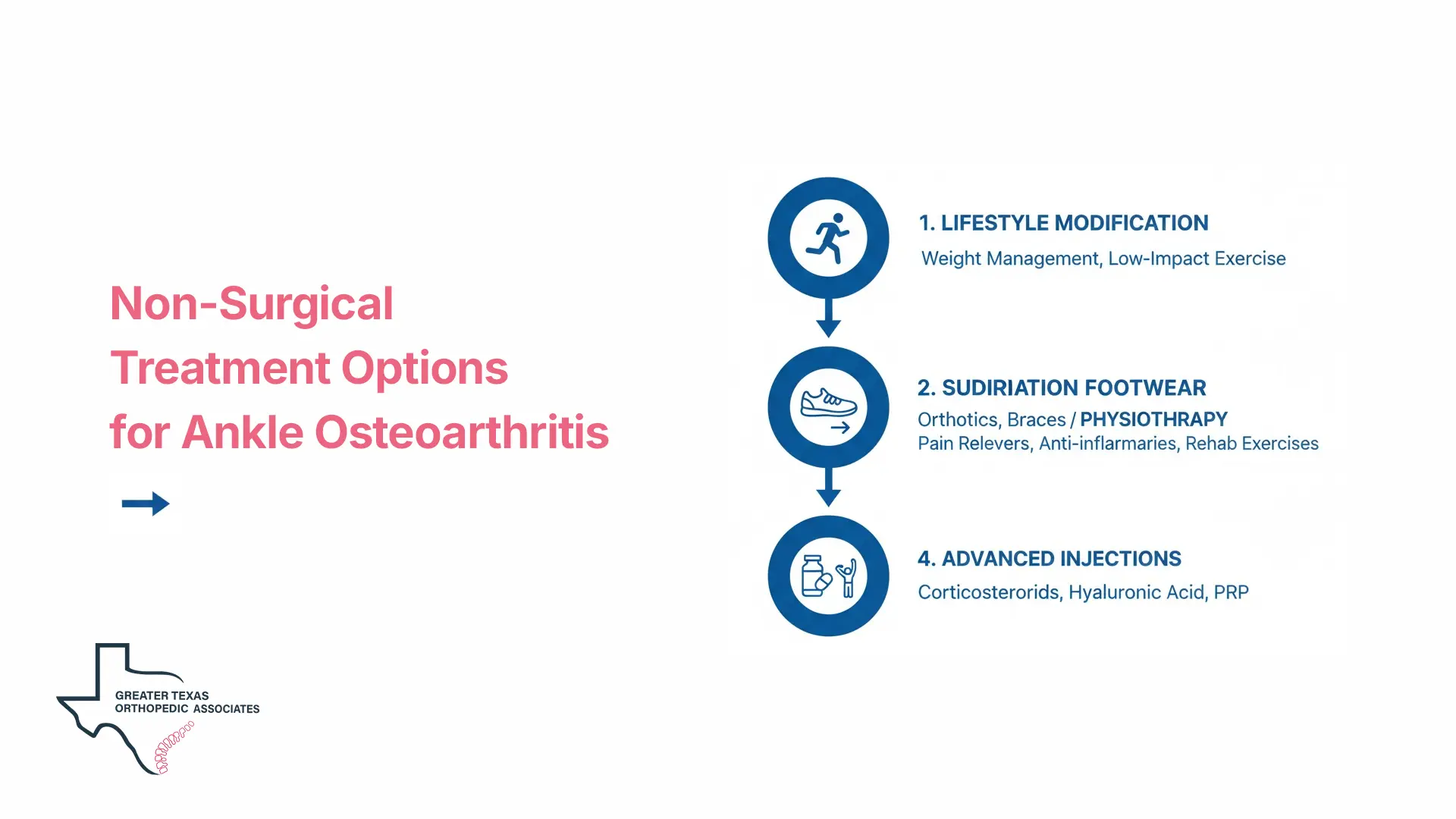

Ankle Osteoarthritis Treatment: Non-Surgical Options

Most experts agree that non-surgical measures should be the first line of defense in ankle osteoarthritis treatment. While these treatments do not “cure” the arthritis, they can significantly manage symptoms and improve daily function. A comprehensive treatment plan for this condition often combines several different approaches.

Lifestyle and Activity Modification

One of the most effective ways to reduce ankle pain is through weight management. Research suggests that even modest weight loss can reduce ankle pain by more than one-third. Patients are also encouraged to modify their activities by switching from high-impact sports, like running or tennis, to low-impact exercises like swimming, cycling, or yoga. Using walking aids, such as a cane or walking stick, can further unload pressure from the affected joint.

Supportive Measures and Footwear

Proper footwear is a cornerstone of this disease treatment. Specialists often recommend high-top boots to stabilize the joint or shoes with “rocker soles,” which have a curved bottom to help the foot roll forward during a step, reducing the need for the ankle to bend. Custom orthotics or shoe inserts can also help correct alignment and provide necessary cushioning.

Medication and Physiotherapy

Pharmacological management typically starts with over-the-counter pain relievers such as paracetamol or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Topical NSAID gels may also be effective for some patients while carrying a lower risk of systemic side effects. Additionally, physiotherapy plays a vital role in strengthening the muscles that support the ankle, which helps absorb the shock of movement.

Advanced Non-Surgical Injections

When standard conservative measures do not provide enough relief, image-guided injections may be considered as part of a broader joint-preserving treatment strategy. These interventions can provide temporary symptom relief, allowing patients to participate more effectively in physical therapy or postpone surgical intervention.

Available injection options include:

- Corticosteroids: These are powerful anti-inflammatory agents injected directly into the joint to dampen swelling and pain. The effects typically last for several weeks or months.

- Hyaluronic Acid: Often referred to as viscosupplementation, these injections aim to lubricate the joint and improve its shock-absorbing capabilities, though results in the ankle can vary.

- Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP): Derived from the patient’s own blood, PRP contains growth factors that may help manage inflammation and kickstart the body’s natural healing processes.

Surgical Options for End-Stage Ankle Arthritis

When conservative care fails, surgical intervention becomes a necessary component of comprehensive ankle osteoarthritis treatment for end-stage disease. The choice of surgery depends on the patient’s age, activity level, and the extent of the joint damage.

Arthroscopy (Keyhole Surgery)

In the earlier stages, an arthroscopy can be performed through small incisions (less than 1 cm). The surgeon uses a tiny camera and small instruments to “tidy up” the joint by removing loose bone fragments, scar tissue, or inflamed tissue (debridement). While this can relieve pain caused by impingement, it does not stop the underlying progression of the arthritis.

Ankle Arthrodesis (Fusion)

Ankle arthrodesis involves removing the worn-out joint surfaces and using screws to “fuse” the tibia to the talus bone. This essentially turns a stiff, painful joint into a stiff, pain-free one. Approximately 2,000 of these procedures are performed annually in the UK, with high success rates.

The primary advantage of fusion is its durability and excellent pain relief, making it the preferred choice for younger, more active patients or those with severe deformity. Although the main ankle joint is stiffened, the surrounding joints in the foot often compensate, allowing the patient to retain about half of their up-and-down foot motion. Most patients can return to activities like walking, cycling, and golf.

Total Ankle Replacement (Arthroplasty)

In a total ankle replacement, the damaged bone ends are resurfaced with metal components, and a plastic insert is placed between to allow for gliding motion. This procedure aims to preserve more of the joint’s natural movement compared to fusion. It is often recommended for older patients (typically over age 55) with lower functional demands or those who have arthritis in several adjacent foot joints.

While ankle replacements provide excellent pain relief, they are generally less durable than hip or knee replacements. Approximately 80% to 90% of ankle replacements are still in place 10 years after surgery, but they may eventually loosen or wear out, requiring a revision surgery.

Recovery and Long-Term Outlook

The recovery timeline for surgery is significant. For both fusion and replacement, patients typically wake up with their foot elevated and in a cast or “backslab”.

- Fusion Recovery: Patients usually wear a cast for 12 weeks and are often not allowed to put weight on the ankle for the first month.

- Replacement Recovery: Patients may only need a cast for about six weeks, as the goal is to begin movement earlier to prevent stiffness.

Following surgery, physiotherapy is essential to rebuild strength. Swelling is common and can persist for up to a year. Patients must also follow strict protocols regarding blood-thinning medication to prevent blood clots while they are immobilized.

Conclusion

Ankle osteoarthritis is a progressive joint condition that often develops years after a traumatic injury. While diagnosis is typically straightforward through clinical examination and imaging, long-term management requires a thoughtful, individualized approach. Depending on disease severity, treatment may range from activity modification and physical therapy to targeted injections or surgical options such as ankle fusion or replacement.